Food for Thought

By David Ren 任大偉

Central to daily living is the consumption of food; dining is the pivot of the workday, social gatherings, and special occasions. Stemming from the unending pursuit of sustenance on the savannah, it is no wonder that food is heavily ingrained into the human psyche and culture. As industrialisation raised agricultural yields, the struggle has disappeared but the deeply-seated calorie-centric focus remains. Why, then, do we understand so little about the nature of flavour?

Flavour

Describing taste is as perplexing as describing colour. Yet, the meaning of sweet, salty, and sour remain intuitively clear. Just as one can theoretically explain colours using wavelengths, taste can be described as chemical reactions on the tongue perceived by the brain. However, flavour is more complex; the flavour of food is intricately intertwined with its smell, taste on the tongue, and texture. To complicate matters further, perception of flavour is affected by the food’s appearance, the consumer’s culture, and psychology. The complex stew of these ingredients creates the perception of “flavour” in the mind. Therefore, it is unsurprising that scientists are only beginning to unravel the science of flavour.

A matter of taste

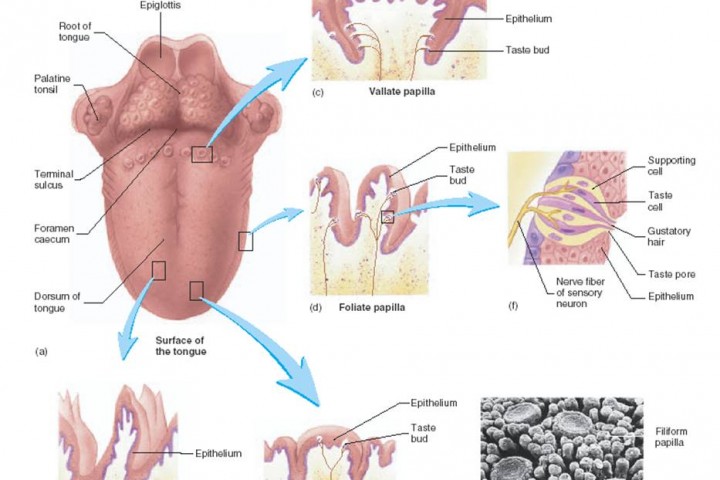

There are five basic tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. Detecting these tastes requires biochemical receptors better known as taste buds. These taste buds are located on fungiform papillae or the small pink bumps on the tongue. Papillae become visible by placing milk or food colouring on the tongue. Contrary to popular belief, this is separate from the infamous “tongue map”, and instead, each taste bud can sense all five tastes.

The numerousness of fungiform papillae varies greatly between individuals and is dictated by genetic factors; approximately one quarter of the population have an abnormally high density of papillae leading to enhanced taste detection [1]. They are known to be supertasters, analogous to those with 20:20 vision. In a study involving supertaster volunteers, it was discovered that 25% of the participants found saccharine (a sweetener) to be sweet and another 25% detected a bitter aftertaste. Supertasters are not only more sensitive to taste but also have the unique ability to taste PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil), a bitter compound [2].

The natural variation in the ability to taste influences the choice of food. Supertasters tend to avoid overly-rich foods such as sugary drinks and desserts, meaning that they are, more often than not, thinner [2].

During tasting, taste buds become damaged and are constantly replenished. In fact, there is a complete cell turnover rate every 10 days, which consumes zinc in the process. As a result, a zinc deficiency decreases the sensation of taste, as does aging.

Olfaction

Flavour is not only limited to taste; it is also manifested through odours from outside and inside the nasal cavity. The olfactory sensation, particularly from the nasal cavity, heavily influences the perception of flavour. This effect is noticeable when one has a cold; foods are less flavourful and thus less identifiable.

The olfactory system is only 2.5cm2 wide but contains 50 million receptor cells. Covered by a layer of mucus, only chemically volatile compounds can dissolve to reach these cells for detection. Thus, odorant molecules are the volatile compounds released from food before and after chewing. A chemical reaction between the odorant and the sensory neuron (nerve cell) in the roof of the nasal cavity is translated into electrochemical signals. This is subsequently transmitted to two olfactory bulbs in the brain via spindly axons embedded in the overlying bone. Information is then relayed to the orbital cortex, where taste and odour are layered with cultural expectations to create “flavour.”

Food for thought

Flavour is a wholly integrated phenomenon across multiple disciplines; both taste and the experience of eating impact the perception of “flavour.” No wonder, then, has it been difficult to pinpoint which substances dictate what makes something flavourful and in what concentrations and combinations. Gastronomy, the science of food, signals a continuation of the hunt for food on the savannah. The scope of the hunt has broadened to consider the aesthetic appeal, the olfactory experience, as well as the personal factors that impact flavour such as genetics, memories, and culture. Although a relatively new science, gastronomy promises to serve flavour into our lives.

References

[1] Super-Tasting Science: Find Out If You’re a “Supertaster”! Scientific American (2012) Retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/super-tasting-science-find-out-if-youre-a-supertaster/

[2] Beckman, M. A Matter of Taste (August 2004). Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/a-matter-of-taste-180940699/?no-ist