MythBusters: The Golden Ratio Around Us

By Aastha Shreeharsh

The world we live in is a big place – a vast expanse of land and sea, in an even bigger cosmic web known as the universe, much of which remains a mystery to us. Making sense of our place in the universe has always been a comfort to humanity in the face of the unknown. The most significant way we do this is by seeking patterns. One such example is the golden ratio.

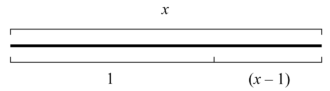

Denoted by the Greek letter phi (φ), the golden ratio is an irrational number – an unending number with infinite digits that cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers, just like π – that has caught the attention of mathematicians, biologists, artists, and architects across the world throughout history [1]. You may be wondering exactly what the golden ratio is and what makes it so special. In order to understand it, let’s assume a variable x, which represents the length of a line segment. The line segment is then divided into two parts, one longer than the other. The length of the longer part is normalized to one and that of the remaining part becomes x – 1, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Division of a line segment of length x into two parts.

So, what would the ratio between x and the longer part be, such that it is equal to that between the longer and shorter parts?

![]()

To find the value of such a “divine proportion” x, we can create a quadratic equation from the relationship above:

![]()

By solving the equation and rejecting the negative solution, we can get x equals to ![]() , approximately 1.618 – this value is the golden ratio. Another famous mathematical concept you may have heard of, the Fibonacci numbers (Fn) forming the Fibonacci sequence, is also closely related to this ratio. Each number in this sequence is the sum of its two predecessors: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5 and so on. The limit of the ratio between each number and its predecessor is, as you can probably tell, the golden ratio, φ. In other words, the higher the Fibonacci numbers, the closer the ratio is to φ.

, approximately 1.618 – this value is the golden ratio. Another famous mathematical concept you may have heard of, the Fibonacci numbers (Fn) forming the Fibonacci sequence, is also closely related to this ratio. Each number in this sequence is the sum of its two predecessors: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5 and so on. The limit of the ratio between each number and its predecessor is, as you can probably tell, the golden ratio, φ. In other words, the higher the Fibonacci numbers, the closer the ratio is to φ.

Often linked to the “beauty of proportion” [2], φ appears in various areas of nature and was said to have inspired artists and architects for centuries. For instance, phyllotaxis (arrangement of leaves around the stem) of certain plants was discovered to be related to the golden ratio. While the angle between successive leaves or leaf pairs can be 90 degrees (decussate pattern) or 180 degrees (distichous pattern), spiral phyllotaxis with an angle close to the golden angle, approximately 137.5 degrees (footnote 1; figure 2), is also prevalent in plants [3]. It is not hard to imagine that such recurrent encounters with this ratio in nature have probably intrigued and awed ancient Greeks and us, as we can identify the incorporation of the ratio into the Parthenon and da Vinci’s The Last Supper [1]. The frequent appearance of the golden ratio in artwork begs the question: Is the golden ratio really a solution to our pursuit of beauty?

Figure 2 Spiral phyllotaxis. (Leaves at consecutive vertical levels are pseudo-colored differently from red to purple.)

Much to our surprise, this might just be our wishful thinking. It may be overthinking that has led us to identify its seemingly overwhelming presence in nature. The human brain loves seeking patterns, so much that perhaps it “favors” the emergence of φ in many of these instances, even when there is no concrete evidence to support the notion [1]. The most compelling case of this myth is the look of nautilus shells.

Nautilus is a sea creature from the same animal class, Cephalopoda, as squids and octopi. Unlike other cephalopods, its home is a beautiful, chambered shell with a spiral. These spirals are known as logarithmic spirals or growth spirals – spirals that keep growing further apart from the innermost curves as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Logarithmic spiral of nautilus.

Nautilus shells are said to be the prime example of the appearance of φ in the natural world, with their logarithmic spirals suggested to have an aspect ratio equivalent to the golden ratio – a deeply held belief that is so popular in no small part due to literature such as Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, renowned scientists and academic institutions like the Smithsonian (footnote 2) perpetuating this “fact” [2].

Yet, if you were to ever inspect a nautilus shell for yourself in real life, you may find the aspect ratio actually closer to 4:3 (1.333) than φ (1.618). When this myth of every nautilus shell having the golden ratio is thought about more deeply, isn’t it kind of odd to think that every single nautilus shell in existence would have the same ratio? It would be more believable if this ratio is varied, even by a few decimal numbers, in different specimens, right?

That’s precisely the same thought a certain researcher by the name of Christopher Bartlett had. He went so far as to surmise that even the 4:3 ratio is not an accurate aspect ratio for most nautilus shells. When 80 shells were examined from the Smithsonian collections, the average ratio came out to be 1.310. All shells had varying ratios with slightly different number; making it absolutely wrong to state that all these spirals somehow have the same measurement, say, 1.6 – a value much closer to the actual value of φ than 1.310 [2].

Why did so many scientists and educators believe this myth then? Well, as covered in this article before, the way humans survive and interpret the world is through seeking out patterns. Sometimes we do this subconsciously against our better judgement, which leads to flawed speculations such as the fantasy of the golden ratio being all around us; however, another great thing about humanity is our insatiable curiosity, which helps us not only create these myths but debunk them just as well.

1 The golden angle: Imagine that we want to divide a circle into two sectors in the golden ratio. After setting up a quadratic equation with the smaller and larger central angles as x degrees and (360 – x) degrees respectively, you will be able to get the golden angle x, which is approximately 137.5 degrees.

2 The Smithsonian Institution: A large museum, education and research complex in Washington, D.C. in the US.

References:

[1] Iosa, M., Morone, G., & Paolucci, S. (2018). Phi in physiology, Psychology and Biomechanics: The golden ratio between myth and science. BioSystems, 165, 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2018.01.001

[2] Bartlett, C. (2018). Nautilus Spirals and the Meta-Golden Ratio Chi. Nexus Network Journal, 21, 641–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-018-0419-3

[3] Strauss, S., Lempe, J., Prusinkiewicz, P., Tsiantis, M., & Smith, R. S. (2020). Phyllotaxis: is the golden angle optimal for light capture?. The New Phytologist, 225(1), 499–510. doi:10.1111/nph.16040